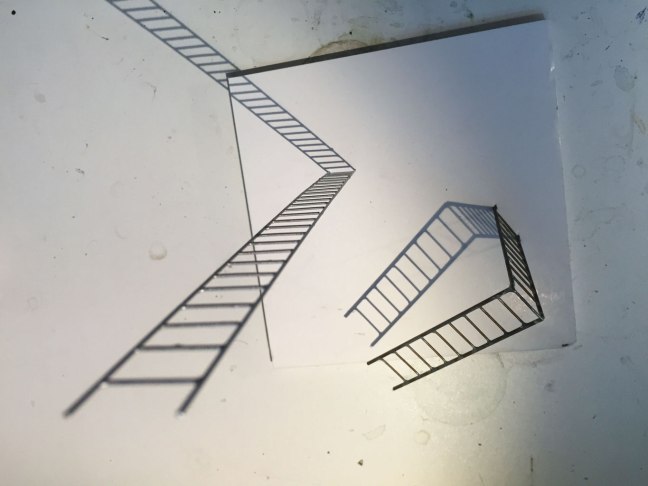

Given the rapid growth of generative AI and society’s addiction to manipulative, corporately controlled online platforms, you might think this is the end of skilled creativity. If anyone can make a film or a song or a novel in seconds, what’s left for skilled artists and craftspeople?

Well, quite a lot, I think.

Yes, we need to fight tooth and nail against the wholesale theft of our work by tech corporations, the loss of livelihoods, and the flooding of culture with soulless, vacuous simulacrums of creativity. Let alone the ecological damage and data harvesting. But I keep thinking about how MP3s and file sharing were going to kill live music, which has, in fact, flourished. At the time, it felt that, after the initial excitement waned, the ubiquity of downloads ended up increasing the value of in-person experience.

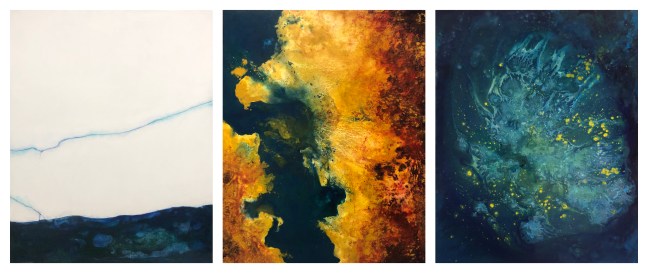

AI is now a spectacle in both the everyday and Debordian senses of the word. But as it is revealed as a kind centripetal force, pushing culture into smooth unoriginality, it will, I believe, remind us of our profound need for human community and connection, and for originality, creativity and craft. It will increase the cultural value of things evidently made by humans, using their skill and expressing something original, meaningful and authentic. It will help us appreciate the rough edges – the grit in the oyster – which allow art to take us to new and challenging places; places we didn’t expect to go.

That is good in itself and gives me hope for the creative sector, both professional and participatory, whether it’s live performance, art manifestly made by human hands, author readings and book signings, craft workshops, communal music-making and dancing… All the myriad points of creative connection that help hold society together.

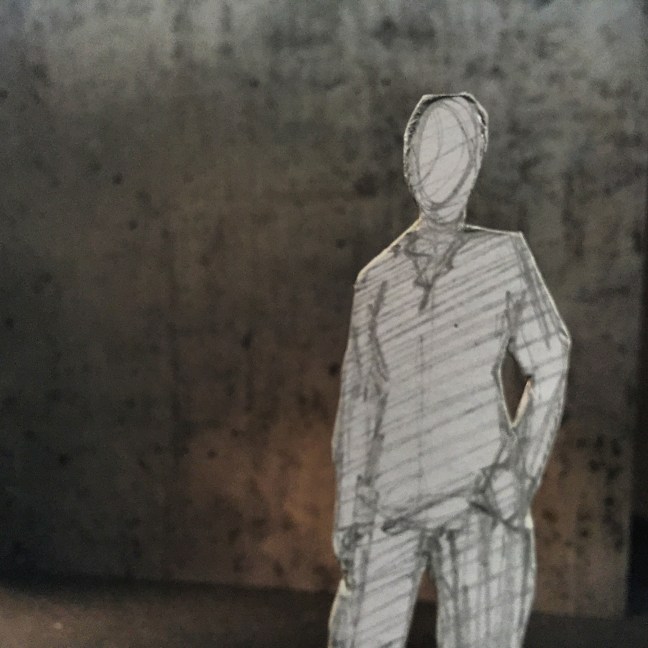

But I have another hope, too; that if more and more people step away from the circus of corporate spectacle, see the atomised, narcissistic and easily exploitable society it fosters, and seek meaning and fulfilment through human creativity – especially co-creativity – we may also find we’re nurturing the conditions needed for meaningful, radical political change.